Most of the objects exhibited in this room have been on display ever since the Museum of Fine Arts was first opened in 1912 and they constitute the core of what was one of the world's finest private collections of Ancient Egyptian art. The collector in question was the Russian orientalist, Vladimir Golenishchev (1836-1947). His collection of around 8,000 items was the first collection of original artworks acquired by the Museum. In 1913 the Museum purchased another range of Ancient-Egyptian artworks from the leading Moscow collector Leonid Ginzburg, which included a relief depicting mourners. Several truly precious gifts were donated to the Museum by Yurii Nechaev-Maltsov, including magnificent Fayum portraits, a gold diadem and a statue of Harpocrates. After the October Revolution items were added to this collection from various museums and private collections. The scholars Boris Farmakovskii, Tamara Borozdina-Kozmina and Alexander Zhivago, whose working lives were intimately bound up with the Museum, donated the Egyptian objects in their possession to the Department of the Ancient East. The Museum's collection was significantly enriched by its acquisition in 1940 of 217 Egyptian items which had belonged to the philologist and art historian, Adrian Prakhov, and were donated to the Museum by his son, Nicolai Prakhov. In the post-war period the collection was expanded further thanks to donations, finds from archaeological excavations and occasional purchases.

The first exhibition in the Ancient Egypt gallery was timed to coincide with the opening of the Museum of Fine Arts and it was prepared by the outstanding Russian Egyptologist, Boris Turaev (1868-1920), and the second one was the work of Professor Vsevolod Pavlov (1899-1972) after World War II. The current exhibition was opened in 1969 by the Head of the Department for the Ancient East, Doctor of Art History Svetlana Khodzhash (1923-2008), who had inspired and organized it.

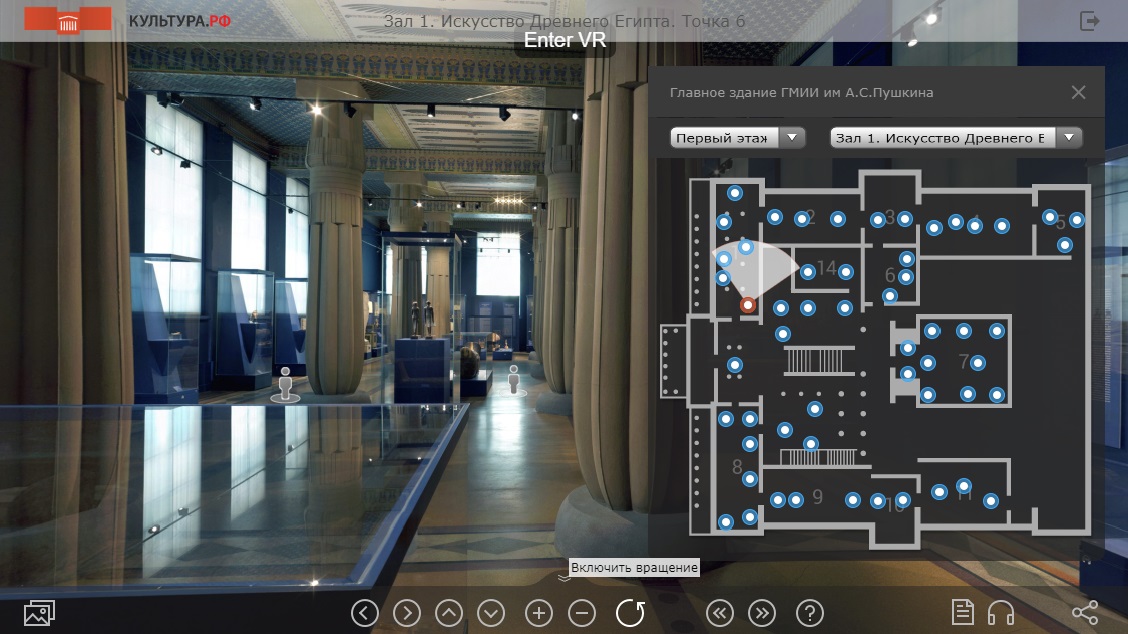

The exhibits in this Room are arranged chronologically, starting with the most ancient – stone tools from the VI-V millennia BC, slate palettes and painted clay vessels from the culture of Naqada I-III (IV millennium BC). The different shapes of pottery and the presence of inscriptions provide us with an idea of artistic craftsmanship in that period. A rare exhibit is a clay dish bearing a depiction of a masked hunter with four dogs on a leash. All the objects were found in burials and bear witness to the funerary rite used in the Pre-Dynastic period. The main features of Ancient-Egyptian art were already manifesting themselves at that time: the pre-determined nature of the religious ideas, adherence to convention, symbolism, monumentality – features which attained the peak of their development after Upper and Lower Egypt had been joined together in a single state (end of the IV millennium BC) in the period of the Old Kingdom (28th-23rd centuries BC).

The Old Kingdom was the time of the first great achievements of Egyptian architecture, when the artistic canon had assumed definitive shape – the canon adhered to by Egyptian craftsmen for several millennia. During this particular period one of the supreme achievements of Egyptian art appeared, namely the sculpted portrait. The principles underlying the decoration of tombs with reliefs on their walls and also the particular methods used for depicting human figures and objects on a flat surface are illustrated by a series of blocks from the tombs of the "Overseer of the Royal Treasury" Isi, lady Merit, the Egyptian Tepemankh (all ca. 25th century BC) and that of the "Gardener of the Pyramid of King Pepi II" Khiiw (ca. 23rd century BC).

The artistic creativity of the Ancient Egyptians was inextricably linked to religious beliefs and the requirements of the funerary rite. In particular, the similarity between the portrait and the individual portrayed stemmed from the belief that each individual had a "double" or Ka – an immortal living essence, which had to have a constant abode within the depiction of the deceased. The idea that all artworks were destined to be eternal and should not contain any chance or transient features determined the nature of the conventional artistic language of Egyptian sculpture: self-contained and indivisible volume, a static appearance and the absence of any superfluous detail. The reliefs and statues of the 5th and 6th dynasties (Showcase No. 6) and the free-standing group, depicting the official Udja-jer with his wife clearly embody the canonical rules for depicting human figures in sculpture.

Showcase No. 6 contains a number of objects which had been placed in a tomb and a unique exhibit – a mask of Pepi II (22nd century BC, 6th dynasty) brought to Russia by Golenishchev from excavations at the site of that king's pyramid.

The Middle Kingdom (22nd-18th centuries BC) is represented by such masterpieces as the statue of King Amenemhet III (19th century BC) and a stela of the "Great Steward" Henenu (21st-20th centuries BC) made of pinkish limestone.

The upper part of the statue of Amenemhet III is a remarkable example of the finest aspects of the sculptured portraits of the Middle Kingdom in its heyday, reflecting interest in the individual and age-dependent characteristics of human beings. Visitors can also see small-scale sculpture (Showcase No.9) including a portrait of King Sesostris II.

Two of the showcases display objects from tombs of the Middle Kingdom deemed essential for the deceased in his life beyond the grave – wooden models of funerary barges and figurines of servants (Showcase No. 10) and also "magic staves", magic female figurines, palettes in the shape of animals and small stone vessels (Showcase No. 9).

The art of the New Kingdom (16th-11th centuries) reflects the triumph of the Egyptian state after the Hyksos had been driven out of Egypt.

What is characteristic of this art, despite the long period of development involved, is on the one hand the intensification of the trend towards realism, interest in the depiction of nature and the endeavour to convey movement, while, on the other, there is a growing inclination towards the decorative, towards refinement and at the same time formalization of the artistic language. These qualities can clearly be seen in works from the period when the pharaohs Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV were in power – fayence vessels, wall- and furniture inlays from Amarna, toilet spoons, game counters, figurines and a limestone head of a youth. One of the masterpieces in this collection – a toilet spoon in the shape of a pink lotus flower and with a handle in the form of a swimming girl – stands out on account of its refined beauty. The exquisite quality of this wooden spoon, in the form of a girl depicted among papyrus thickets, and a small wooden oval box with its sliding lid encrusted with fayence inlays are remarkable examples of the art of Ancient Egyptian carvers.

An undisputed masterpiece in the Egyptian collection of the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts is the pair of figures representing the priest Amenhotep and his wife, the priestess Rannai dating from the reign of atshesput. HHatshepsut. The figurines have been worked from rare ebony imported into Egypt from the southern regions of Africa: the eyes of the husband and wife are encrusted with paste. These elegant figures with their delicate limbs and distinguished by the refined use of detail – the gold-plated jewellery and the luxuriant wig worn by the priestess – bring us a glimpse of the inimitable and easily recognizable beauty of the finest works of Ancient-Egyptian art.

Showcase No. 14 contains a relief from a single tomb dating from the end of the 18th dynasty in Saqqara bearing a depiction of the mourners. The dynamic composition and the depiction of human figures shown at complex angles render this fragment of a funerary procession dramatic and expressive.

The rituals concerned with afterlife, which played such an enormous part in the religion of the Egyptians, led to the appearance of various articles directly linked with the funerary cult and the ideas about the fate of the deceased after death. These include coffins, canopic jars (vessels for the preservation of the embalmed internal organs of the deceased), funerary masks, small figures known as shabti, with the wooden containers in which they were kept, and figurines of deities. In one of the showcases there is a swaddled mummy of the priest Hor-ha covered with a net consisting of fayence beads, the head of a female mummy and also mummies of sacred animals – the cat and the falcon. Next to these on a podium is a set of canopic jars with lids in the shape of heads of four sons of the god Horus. The coffins exhibited in this Room date from various periods starting from the III millennium BC (a simple clay box, on the lid of which there is a depiction in relief of a boy in a foetal position). The most colourful coffins, which are covered all over with painted decoration, are those dating from the New Kingdom and they are laid out in the central part of the Room. The two stone sarcophagi date from the second half of the Ist millennium BC.

Some of the showcases display numerous deities from the Egyptian pantheon. They have been fashioned from bronze, stone (the statues of Osiris in Showcases Nos. 24 and 26) and there are also small figures of gods made out of cornelian and rock crystal (Showcase No. 12). A figurine of Nefertum, god of vegetation, has been cast in silver (Showcase No. 18) and the sacred ibis of the god Thoth (Showcase No. 12) has been depicted in white stone and has a bronze head and paws. All the figures stand out on account of the high quality of the casting and the fine workmanship of the details.

A considerable proportion of the exhibits consists of alabaster vessels, fayence bowls, painted clay jugs, bronze situlae (ritual vessels) and mirrors, bronze weapons, jewellery fashioned from semi-precious stones and from Egyptian fayence.

Some statues and portrait sculptures (Showcase No. 26) date from the Late Period (Ist millennium BC). Among these a granite statue of a queen stands out, whose face has been depicted with vividly expressed features (first half of the 7th century BC). The portraits from the period of the Saite Dynasty (late 7th and 6th centuries) have been executed in hard stone in imitation of their ancient models and they reflect the craftsmen's endeavour to achieve both perfection of form and ideal quality in their working of the stone surfaces. The Saite period constituted a new peak in the development of artistic craftsmanship.

The so-called "Sculptor's Corner" enables visitors to envisage the process involved in the creation of reliefs and works of sculpture by Egyptian craftsmen: they can see unfinished reliefs or copies made by craftsmen's pupils and also drawings on sherds of limestone (ostraca).