With the traditional graphic technics – black chalk, pencil, watercolours, gouache – the artists were solving new esthetic problems occurring at the turn of the 19th and 20th century.

Gustav Klimt, the main representative of the Viennese Art Nouveau, was famous for his phenomenal drawing skills. He earned a very special place not only in Austrian, but also in world art. His drawings influenced the art of young artists, first of all Egon Schiele, who started his art career at the time when Klimt reached the peak of his career. With the fundamentals adopted from Klimt, Schiele developed his personal unique style, that marked the turn from Art Nouveau to Expressionism.

The artworks by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele entered the Albertina collection during the lifetime of the artists. Nowadays, a century later, the number of drawings has increased to 170 drawings by Klimt and to 140 by Schiele, in addition to about 40 works that are in long-term storage at the museum.

Klimt’s drawings became extremely popular among collectors and connoisseurs at the end of his life and after his death in 1918. Although Klimt the painter subsequently overshadowed Klimt the draughtsman, the recent studies and cataloguization of his graphic work have made it fully possible to assess the role of drawing in his art. After his death, about 2,500 drawings that he had not sold, given away or destroyed were found in his studio. Overall, more than 4,000 of his drawings are known today.

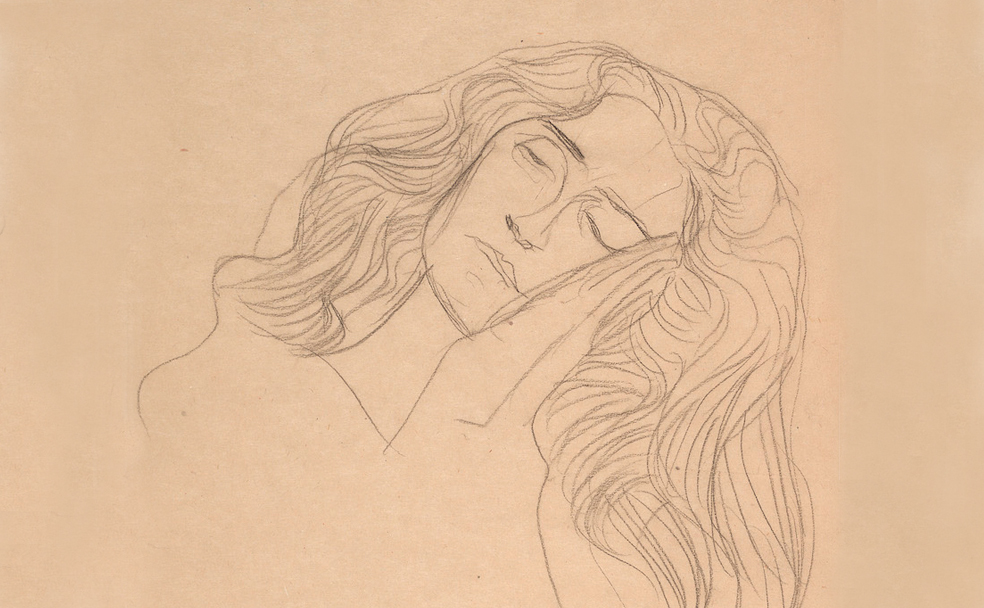

Most of the artist's drawings are related to certain paintings. Klimt never revealed his artistic ideas either in writing or orally, only his drawings help to understand his creative methods. In his multi-figured compositions, Klimt payed great attention to the studies of each figure. His oeuvre includes a series of drawings depicting the same motive or posture.

A major part of the exhibited drawings are female portraits (Portraits of Serena Lederer, Paula Zuckerkandl, etc.) In these studies, Klimt was trying to find a certain posture and composition of the portrait that would help to reveal the model’s personality from the artist's perspective.

Klimt developed a revolutionary approach to the depiction of nude female figures. Unlike in his paintings, he interprets the erotic aspects more explicitly in his drawings. Some of the studies were related to Klimt’s work on the pictorial compositions, but most of them are autonomous (Reclining Female Nude)

During his lifetime, the artist evolved his graphic style. His early drawings, with their almost photorealistic details, graphic details indicate his thorough academic training. But the features that would later become the constant of Klimt’s graphic manner had already appeared in his early works: the primacy of the linear principle, and the expressiveness of the contour, in which precision is combined with sensuality. The special place in the artist’s oeuvre belongs to the drawings for the magazine «Ver Sacrum» (1898). Built on contrasts of black and white (Initial D) they may be called paragons of the Art Nouveau style in graphic art. Over time, the elements of stylization and geometrization of form are occurring more often.

From about 1897 onwards, Klimt drew with black chalk on brown wrapping paper. Later (circa 1903-1904), he began to use smoother Japan paper along with graphite pencil (Seated Female Semi-Nude). The crisp and precise graphite lines with their metallic lustre give the drawings a characteristic look; they correspond chronologically to the “golden style” in Klimt’s paintings (Standing Pregnant Female Nude). In subsequent years (after about 1908 and especially after 1910), the lines in Klimt’s drawings became more free, uninhibited “pictorial” and even broken and nervous at times, showing the artist’s inner turmoil (Standing Woman with Lowered Arms).

Klimt’s drawing style with its expressive contours served as a model for Egon Schiele. The experience of the decorative stylization of nature amassed by Viennese Art Nouveau was reinterpreted and applied to solve new problems posed by the aesthetics of Expressionism.

Schiele considered himself to be first and foremost a painter and wanted people to see him as such. However, critics and art lovers often hold Schiele the draughtsman higher than Schiele the painter. For Schiele, drawing was as natural as breathing. Lines and contours play such an important role in Schiele’s paintings that one can call drawing the foundation of his painterly oeuvre. He left about 3,000 works on paper behind – drawings, watercolours and gouaches.

Schiele’s earliest drawings at the exhibition date from 1906 (Self-Portrait, Bust of Voltaire), a starting point that allows viewers to appreciate the rapid evolution that his art underwent over the following years. A series of postcard designs (circa 1909) shows that the artist had already mastered the style of the Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte, marked by decorativeness and geometric stylization. At this time he was strongly influenced by Gustav Klimt.

In the second half of 1909, Schiele began to break free from this influence until he finally developed his own personal style in 1910. Decorativeness and elegance gave way to expression and emotional tension (The Painter Max Oppenheimer). The contour became the main means of expression in Schiele’s drawings. The transition from Art Nouveau to Expressionism was marked by the negation of “beauty” as understood by idealistic aesthetics and signified the effacement of boundaries between the beautiful and the ugly. The limits of art expanded, and began to include what had earlier been considered anti-aesthetic. In his watercolours and gouaches, Schiele used colour to augment the emotional intensity of his work. In some works, made in 1913 and 1914, the hatching becomes angular and “prickly”.

Schiele’s drawings of subsequent years (1915-1917) show signs of an increasing penchant for realism and for the depiction of volume and plasticity (Nude on Her Stomach). His 1918 drawings make use of a single continuous contour line delineating the entire figure – a pure contour that is only occasionally embellished by scant hatching. Schiele attains an unerring precision of line, laconism, and an economy of visual means.

In the years 1910-1911, Schiele often drew children often and these drawings refer to his first Expressionistic works (Girl with Ocher-yellow Dress). Schiele the draughtsman made many portraits that often represent people from his “inner circle”.

Schiele’s self-portraits are a very special phenomenon in the history of art. The artist made different images of himself, trying on “masks”, playing roles, and making faces; in some self-portraits, he even depicted himself naked. All of these were visual symbols of the fragility of his inner self that tended to fall apart into incompatible elements. Schiele assigned a lot of importance to expressive gestures, poses and mimics, both in his self-portraits as well as in his portraits of other people. Schiele invented and staged a body language of his own: far from natural expressions of real emotions, all the models’ poses were dictated by the artist (Nude Self-Portrait. Grimace).

Many of Schiele’s graphic works depict female models that are often nude. Just like Rodin and Klimt he kept models in his studio, where he observed their behavior. Schiele had no forbidden themes in this genre and lifted all the taboos. His utmost candidness in the treatment of erotic themes became an aesthetic principle of sorts (Seated Nude).

The figures in Schiele’s drawings are taken out of their social and everyday context and placed into the abstract field of the paper sheet, with a lack of reference points. His characters exist outside of time and space.

A special place in Schiele’s graphic oeuvre belongs to thirteen watercolours and drawings made during his stay in prison in the spring of 1912, which he experienced as a humiliating infringement on his freedom. Two of these drawings are shown at the exhibition (The Door to the Open, My Wandering Path Leads over Abysses): they create the impression of documentary eyewitness accounts.

Vitaly Mishin, the curator of the exhibition: “I believe that for many Russian visitors this exhibition will open new esthetic horizons. It will expand the usual perception of beauty, expressiveness and, perhaps even the limits of what is permitted in art. Due to the different historic circumstances, the Parisian avant-garde of the beginning of the 20th century is better known in our country than the art life of Vienna from around 1900. The same can be said about drawings, despite the fact that for a long time, Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele have been recognized as two of the most outstanding artists in the history of art. But to better understand the graphic charm and powerful energy of their drawings you have to see them with your own eyes. Book reproductions and pictures on the internet are not able to reproduce even a fraction of the artistic qualities in the drawings of these great Austrian artists. The display at The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts is based on the rich collection of the Albertina museum and gives us a rare opportunity to deeply understand the evolution of both masters, their creative method, and their unique esthetic world.

Curators of the project: Vitaly Mishin (leading research associate of the 19 th and 20th Century European and American Art Department) and Chrisof Metzger (Albertina, Vienna)

Recommended age of visitors 18+